Three Holes in a Parachute - some thoughts on material value in biography

by Amanprit Sandhu 3/14/2019

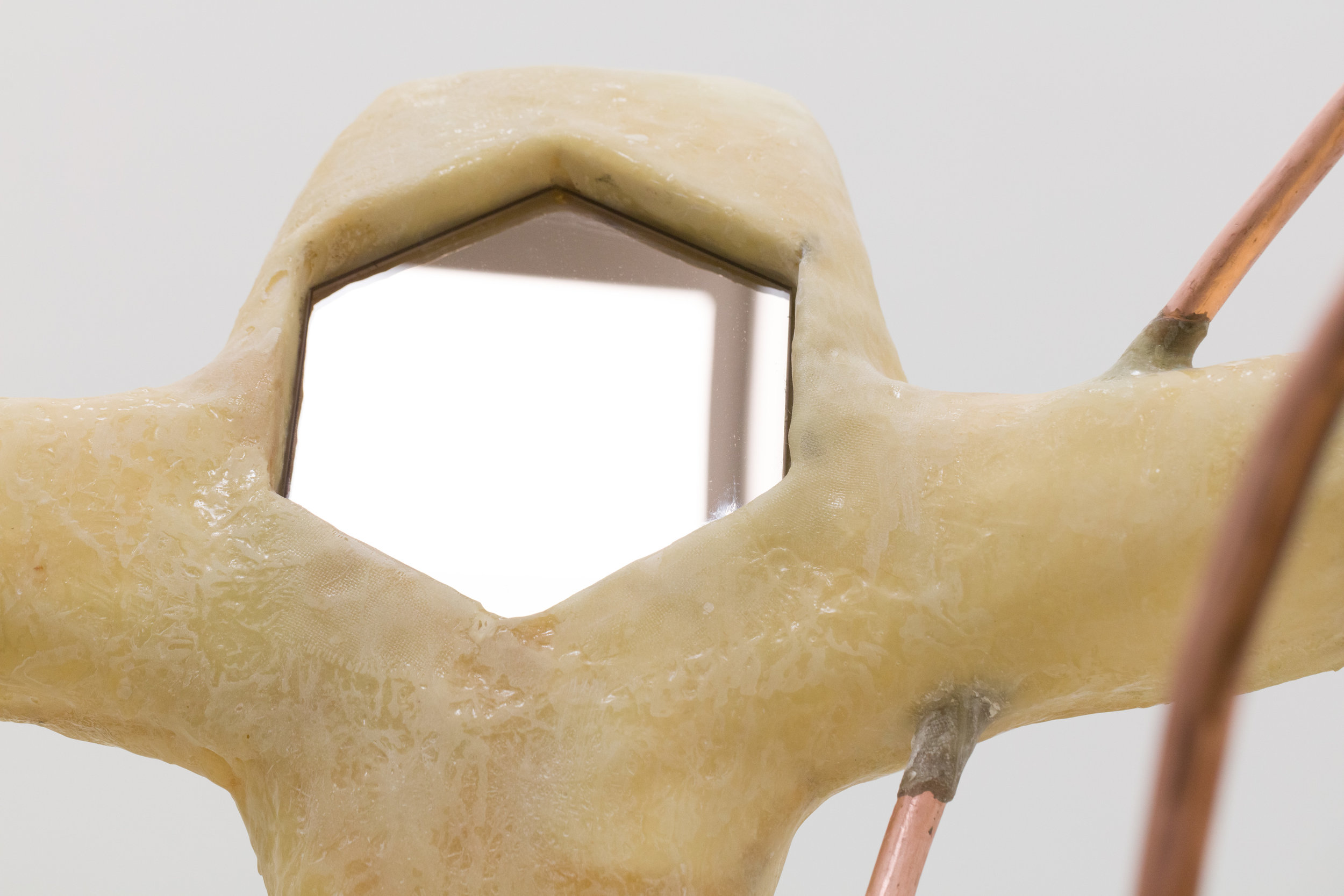

Throwing Stones, 2019 Fiberglass, foam, rubber hose, copper tube, mirror 58 x 78.25 x 32.25 inches

Over the past six weeks Jason Bailer Losh has been sending me a steady flow of images via WhatsApp messenger of his new works as they have transformed from facsimiles of ubiquitous mid-century chairs, to sculptures that imbue a wholly different quality and meaning. Throughout the exchange we have shared conversations about his current touchstones, from Noah Purifoy’s use of objects taken from the communities he knew and lived within, to sculptor and designer Isamu Noguchi’s art works setting the physical parameters for dancer and choreographer Martha Graham’s productions. Along the way we have managed to move away from conversations about the pedestal and the armature of the artist’s studio, discourses that have both sustained and held back Losh’s work and readings of it. We have discussed the slippages between sculpture, object and design, and what it means for Losh to work materially within his means.

In Three Holes in a Parachute Losh revisits the intervention staged by his family in winter 2015. The experience challenged the artist to re-evaluate his priorities and commitment towards his wife and two young children. Spending money on his art work had left his family in the hole, with limited return and little affirmation received from the LA art community through the offer of exhibitions. Scrutinized and confronted by those closest to him, the artist uses the event as a departure point to reflect on familial relations and in turn sculptures’ relationship to social experience.

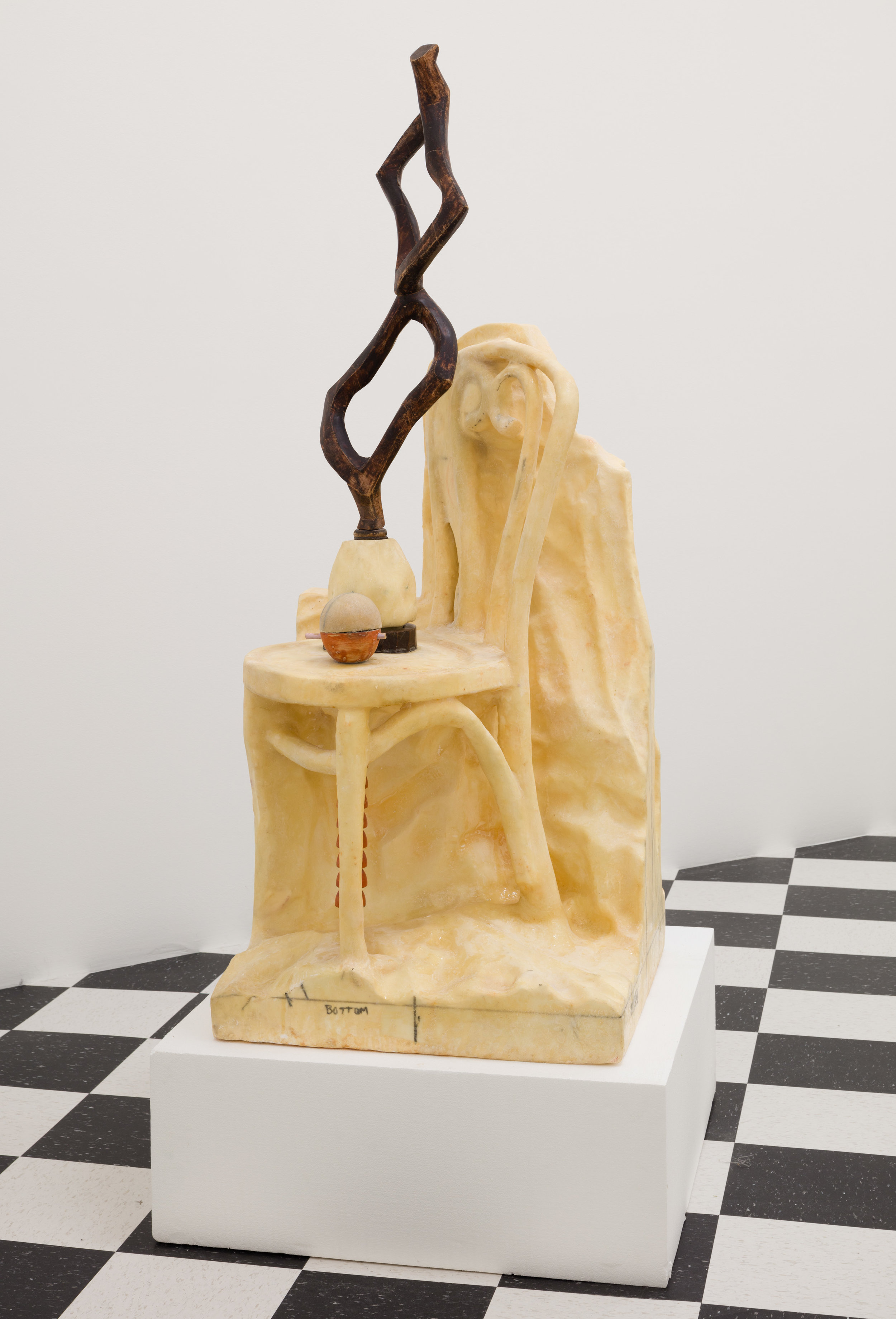

The chairs used by family members involved in the intervention (including his father, father-in-law, mother, mother in law and wife) are re-imagined and re-presented, each sculpture taking on its own personality and role within the exhibition space.

Cut and carved from single blocks of EPS foam, Losh has employed technical skills passed down to him by his father a carpenter, skills he says he has tried to hide as they are no longer valued. The usually light weight and rigid foam material has been resurfaced using fiberglass and epoxy resin and then sanded. This process of reworking allows the works to move beyond the representation of the objects they depict, instead they take on new material qualities that play with weight and volume and possess a thingliness that sits outside of the familiar.

1:1 in scale, these are not ergonomic or comfortable sculptures to support a posture or sustain a stance, instead they are precarious works that teeter on the black and white linoleum flooring or appear sunken into foam bases. Two appear frozen in motion, falling backwards, and others are dwarfed in size by the objects that are set into them.

Collectively they form armature for a narrative that makes a reference to domesticity perhaps at odds with ones’ own aspirations: simultaneously support structure and obstacle. This narrative is propelled through the choice of objects used which include the artists second wedding ring placed at the base of one of the works, a horseshoe associated with prosperity, the ornamental gourd set within the base of a stool, industrial copper tubing, and wooden carved panels and decorative mirrors set into the sculptures.

The use of readily accessible objects and everyday materials such as foam, cardboard and plaster in Losh’s work is significant. Previous art works have involved using cardboard cast in bronze, and sculptures created from throw away materials that take on material qualities and value at odds with its humble beginnings. The detritus of everyday life is incorporated into works that at first glance appear to share and pay homage to the aesthetics of modernist sculpture. However, Losh’s practice operates across a range of registers that touch upon class, labour and craft.

His works draw on biography, and in this exhibition the difficult subject of financial solvency. Informed by his background growing up in the small mid-western town of Denison Iowa, the economy of means by which Losh approaches making is directly influenced by an inherited biography that has been passed down to him.

In turn there is a parallel conversation at play between generations of men in Losh’s family, and how they might understand and relate to one another through their craft of object making. This is evident in the notes the artist receives from his father in law which accompany the packages of objects that are sent to Losh to make his art work. A decade long exchange between two sculptors, there is an economy of words in the notes that never goes beyond the functional and formal qualities of the description of the objects.

To revisit and recount one’s actions and consequences as Losh has done in Three Holes in a Parachute is a cathartic experience, doubly so for the artist as he plans to relocate to the east coast. Whilst in earlier works the objects received from Losh’s father-in-law was a way to displace formal decisions from his artistic process, this new body of work has required Losh to do the reverse, and instead carve through and cut open his biography, taking his work into a new direction in the process.

Amanprit Sandhu is a curator based in London, UK. At the time of this essay she was working as a programe curator at Camden Arts Centre, London and is co-founder of DAM PROJECTS. In 2014 she began a conversation with Losh on ‘progressive formalism’ and its contemporary manifestations.

Planted in Prose, 2019 Oil on canvas stretched on panel 96 x 72 x 1.5 inches